Some Corner of a Foreign Field That Is Forever England

Pete was pacing the sidewalk in his black patent oxfords; left foot, right foot, left foot, right foot, an agitated march-in-place as he looked anxiously back and forth, up and down the street. We noticed him because of his hat—something like the hats worn by London’s Royal Palace Guard—tall, black, and furry, with a gold-chain chin strap.

As we slowed the car, wondering out loud if we should stop and ask him about himself, the tall, slim soldier quick-stepped over to us, stiff in his full-length blue wool coat, the brass buttons polished to a shine, and a red paper poppy pinned over his heart. In his left, white-gloved hand, he carried a shiny bugle. It was November 11th.

The Dutch do not share the same commemoration day as the Commonwealth Remembrance Day; they set aside two days in May. On the 4th, they remember the victims of war, and then, on the 5th, celebrate liberation in 1945 from German occupation by Allied forces. But, with the close proximity to Flanders Fields, and the special relationship with countries that liberated the Netherlands, pop-up commemorations for the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month do happen with some regularity.

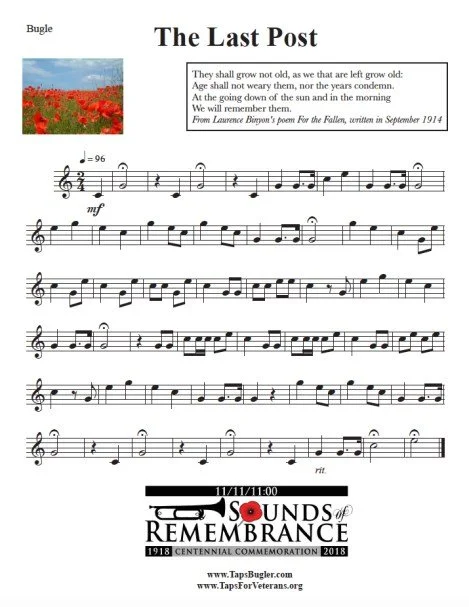

Pete quickly introduced himself, revealing a British accent to match the hat. Would you mind very much giving me a ride? Hardly waiting for an answer, he pulled off his hat, clambered into the back seat and spilled his story. I’m a bugler in a special military division that stays in the area for a few weeks every year - we have assignments every day in the surrounding countryside - we’re dropped off by volunteers to play The Last Post for Remembrance Day ceremonies. He had come to play for a very special ceremony in our neighbourhood at 11:00. …and I’ve been dropped off at the wrong cemetery! He finished. I glanced at my watch - it was 10:43. An AWOL trumpeter!

We sped off toward the only other cemetery in town with a tidy row of matching white headstones. In record time, we pulled up at the curb where a group of well-dressed men and women carrying single red roses were looking up and down the street with equal anxiety – clearly in search of their bugler.

Quick introductions revealed some of the rose-holders were Dutch, and the others were from England. The visiting Brits were staying with the families who had housed their loved ones during the war. It was an intimate group—about 15 people —and they invited us to join the service. It was an honour we couldn’t refuse.

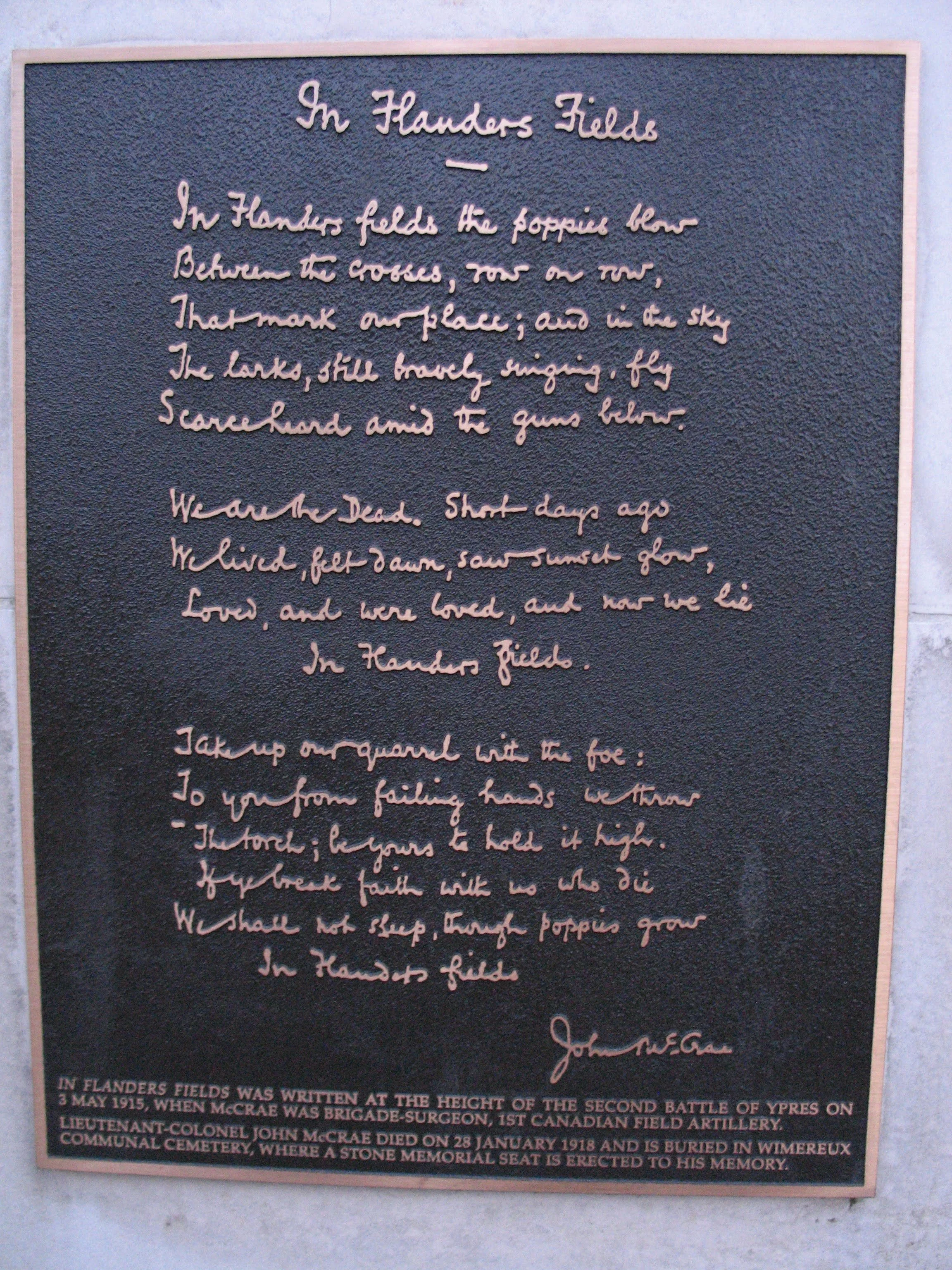

We’ve made it a practice to visit war graves as we travel around the region; the massive Tyne Cot cemetery at Passchendaele, Belgium, where more than 11,000 soldiers lay, most of them unknown; Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery near Nijmegen in the Netherlands where over 2000 Canadian soldiers are buried; tiny walled plots in Belgian farmers’ fields with two or three or six headstones marking the fallen where they fell; and the Essex Farm Cemetery just outside of Ypres, next to the bunker where Canadian Lieutenant John McRae, in 1915, wrote In Flanders Fields.

I take my time to wander the rows, trying to fathom the unfathomable, paying particular attention to the short inscriptions at the bottom of some stones, because a family in deepest grief had to choose those few words that will forever be etched under the name of their beloved.

~ At the rising of the sun and the setting of the sun, we will remember them

~ He died so that we could live

~ Sometime somewhere we will understand

~ It is as if the sun had gone out

~ There is nothing more to give. May you enjoy the liberty for which he died

In most Commonwealth War Grave cemeteries, the stones are uniform white rectangles, lined up with military precision and, if possible, carved from Portland stone, ensuring that every casualty is commemorated equally. The rounded top is neutral, suitable for all faiths and none. Next of kin are invited to choose a faith symbol, and supply a short personal inscription. But, many stones lack epitaphs; New Zealand believed that, to ensure equality, it was best not to allow personal inscriptions; some families were unable to supply the information within the timeline; and, during World War I, while most countries, including Canada, covered the cost of the inscriptions, Brits were made to pay 3½ pence per letter, which meant many families couldn’t afford it.

As Arthur and I walked with our bugler toward the row of twenty war graves in the Sittard General Cemetery, we were each handed a single red rose to hold while the vicar, in full military regalia, gave a short sermon. Pete, waiting patiently for his moment, lifted his bugle and the notes of The Last Post rang out as clear as the frosty blue morning, long and pure, across the cemetery and beyond as the group fell silent. When the last tone had faded, I walked forward to place my rose at the grave of Lieutenant Bennet James Farquharson Remnant of Oxfordshire, England. Age 20.

He was known to his family as Ben.

Ben was fighting with the 1st Battalion, Rifle Brigade when he was killed on January 26th, 1945, the last day of Operation Blacklock, the British assault that cleared the Germans from an area just north of my Dutch home. His parents, Peter and Betty, and sister Dawn chose for his epitaph, a line from the poem The Soldier by Rupert Brooke:

Some Corner of a Foreign Field That Is Forever England.

We looked around for Pete after the service, but he’d already run back to the street to catch his ride to the next ceremony.

Lest we forget.